Astronomers typically study objects that are visible night after night or explode suddenly, like supernovas, but Casey Law is scouring vast amounts of data in search of bright objects that disappear, never to be seen again.

That search turned up the first of what may be many “ghost” objects in the sky: in this case, an extremely bright source of radio emissions that blazed into existence in the 1990s and then faded out over next 25 years.

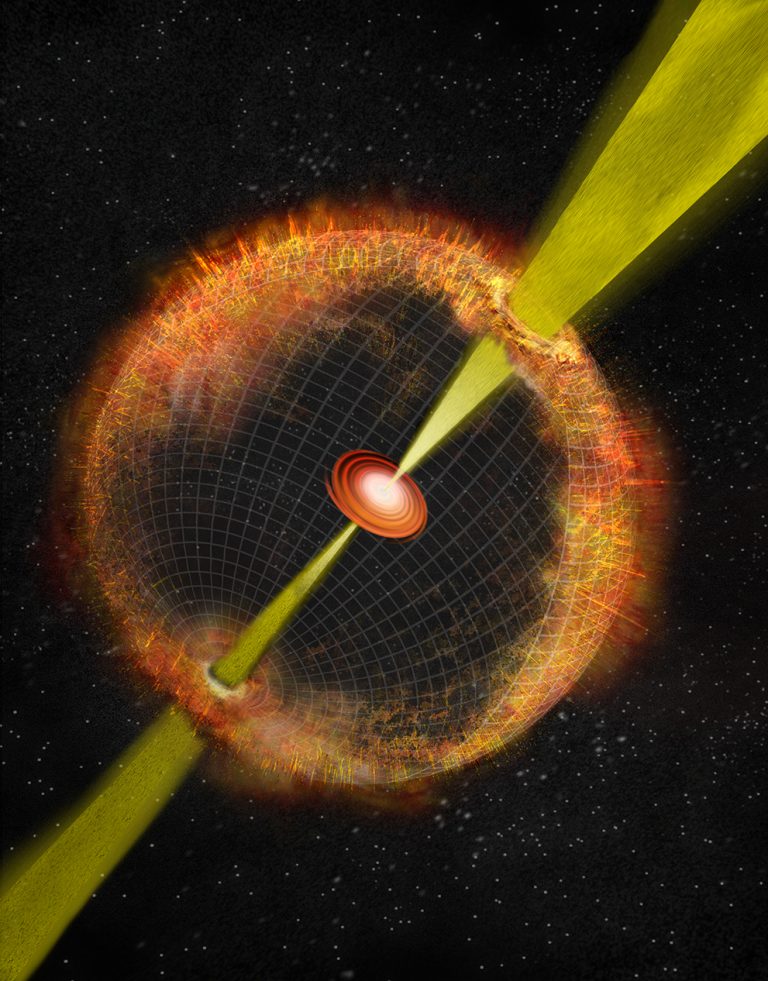

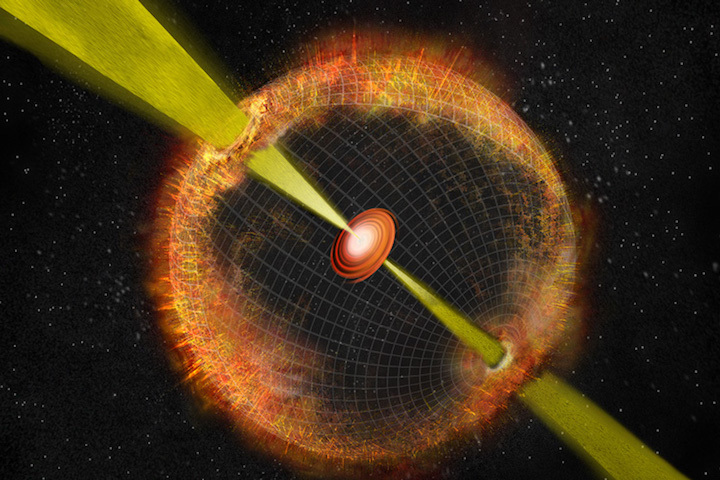

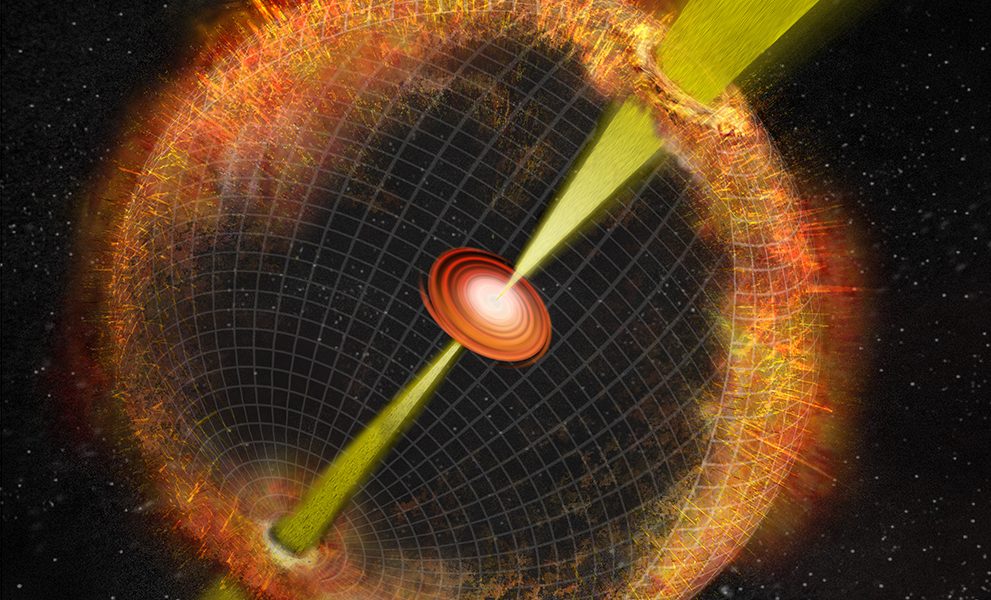

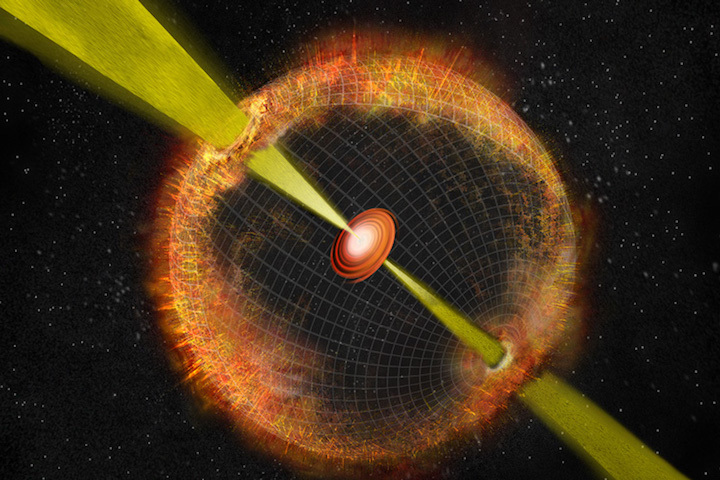

Based on the extreme brightness of the radio source and the type of galaxy in which the flare-up occurred, Law argues that it was the afterglow of the explosion of a massive star, which would have emitted an undetected long-duration gamma-ray burst. Gamma-ray bursts, whose origins are still contentious, are among the most intense flashes in the universe because much of their explosive energy is collimated into a tight beam, like that from a lighthouse.

“We believe we are the first to find evidence for gamma-ray bursts that could not be detected with a gamma-ray telescope,” said Law, an assistant research astronomer in the Department of Astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley. “These are known as ‘orphan’ gamma-ray bursts, and many more such orphan GRBs are expected in new radio surveys that are now underway.”

Gamma-ray bursts, such as that detected last year accompanying gravitational waves from the merger of two neutron stars, are rarely seen because the source of the gamma rays – a relativistic jet of material emerging from the explosive merger – must be pointing directly at Earth. Perhaps only one in 100 explosions can be seen from Earth by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, for example.

The fact that these explosions are followed by a decades-long radio afterglow provides a way for astronomers to find the rest of these explosive events, not just those heralded by a gamma-ray burst.

Finding many more gamma-ray bursts will help resolve a major question in astronomy today: What are these massive stellar explosions that generate gamma-ray bursts, and what’s left behind afterward?

Law favors the theory that the explosion – whether preceded by the merger of two very large stars or neutron stars, or marking the death of a single, massive star – produces a rapidly spinning and highly magnetized neutron star, known as a magnetar. The surrounding matter emits intense radio waves that slowly fade away, during which time the magnetar spins down and occasionally emits fast radio bursts, another mysterious “transient” event in the universe.

He and his colleagues detail their observations and conclusions in an article recently accepted by the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters and accessible now on the arXiv server.

The value of archived data

The radio source (FIRST J141918.9+394036), now too faint to show up in sky surveys but still detectable by large radio telescopes, was a bright spot in a radio survey of the sky conducted in the early 1990s by the Very Large Array in New Mexico. It was on a par with the brightest radio sources in the universe: quasars and active galactic nuclei fueled by stars and gas falling into the massive black holes in the cores of galaxies.

An artist’s depiction of a gamma ray burst, emitted in oppositely directed beams after a massive stellar explosion. While the beams often miss Earth, these explosions create a telltale transient radio glow that can be detected. NRAO image.

“We thought, ‘That was weird,’” Law said. “Its peak brightness in the ‘90s was quite high, so it was a big, big change: about a factor of 50 decrease in brightness. We basically went through every radio survey, every radio dataset we could find, every archive in the world to piece together the story of what happened to this thing.”

He and his colleagues discovered 10 other sets of radio observations of that area of the sky, in the constellation Boötes, that allowed them to document the object’s appearance and disappearance.

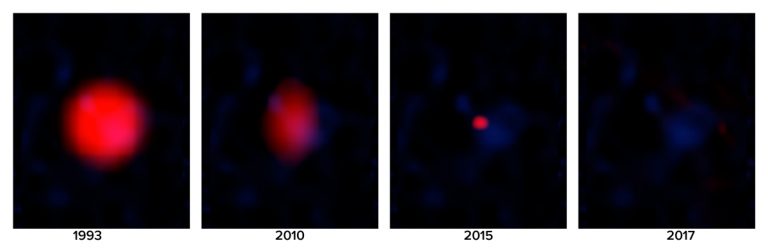

They concluded that the radio emissions first reached Earth in 1992 or 1993, though their first detection was around the source’s peak brightness in 1994. It then faded away over a period of 23 years. It was fainter in a 2010 survey and barely visible in 2015. It was invisible in a 2017 Very Large Array Sky Survey.

The mystery object is located inside a dwarf galaxy 284 million light years from Earth that is still forming stars: a special environment that has previously been associated with fast radio bursts and, independently, gamma-ray bursts and the formation of magnetars. This led Law to conclude that the radio emissions from the dwarf galaxy were the 25-year-long afterglow from the explosion of a massive star, perhaps more than 40 times the mass of the sun, which would have produced a long gamma-ray burst that went undetected. Most GRBs last less than a minute.

One theory is that the resulting magnetar, because of its high rotation rate and huge magnetic fields, emits periodic fast radio bursts – each just a millisecond long – as it winds down to a run-of-the-mill pulsar.

While Law is enthused by the possibility of uncovering many more orphan gamma-ray bursts, he emphasizes the value of mining archived observational data in search of astronomical events that pop up and fade out over years to decades — what his team jokingly refers to as “anti-transients.”

“Part of the story is about how much of the sky is changing, even on this long time scale, and how hard it is to test that,” he said. “It is also partly about the value of new data science techniques. Pulling out information from these rich and diverse data sets is helping us do good science.”

Law’s co-authors are Bryan Gaensler of the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute, Brian Metzger and Lorenzo Sironi of Columbia University and Eran Ofek of the Weizmann Institute in Israel. Law’s research is supported by the National Science Foundation (1611606).

RELATED INFORMATION

Quelle: Berkeley University

+++

Astronomers comparing data from an ongoing major survey of the sky using the National Science Foundation’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) to data from earlier surveys likely have made the first discovery of the afterglow of a powerful gamma ray burst that produced no gamma rays detectable at Earth. The unprecedented discovery of this “orphan” gamma ray burst (GRB) offers key clues to understanding the aftermath of these highly energetic events.

“GRBs emit their gamma rays in narrowly focused beams. In this case, we believe the beams were pointed away from Earth, so gamma ray telescopes did not see this event. What we found is the radio emission from the explosion’s aftermath, acting over time much as we expect for a GRB,” said Casey Law, of the University of California, Berkeley.

While searching through data from the first epoch of observing for the VLA Sky Survey (VLASS) in late 2017, the astronomers noted that an object that appeared in images from an earlier VLA survey in 1994 did not appear in the VLASS images. They then searched for additional data from the VLA and other radio telescopes. They found that observations of the object’s location in the sky dating back as far as 1975 had not detected it until it first appeared in a VLA image from 1993.

The object then appeared in several images made with the VLA and the Westerbork telescope in the Netherlands from 1993 through 2015. The object, dubbed FIRST J1419+3940, is in the outskirts of a galaxy more than 280 million light-years from Earth.

“This is a small galaxy with active star formation, similar to others in which we have seen the type of GRBs that result when a very massive star explodes,” Law said.

The strength of the radio emission from J1419+3940 and the fact that it slowly evolved over time support the idea that it is the afterglow of such a GRB, the scientists said. They suggested that the explosion and burst of gamma rays should have been seen sometime in 1992 or 1993.

However, after searching databases from gamma ray observatories, “We could find no convincing candidate for a detected GRB from this galaxy,” Law said.

While there are other possible explanations for the object’s behavior, the scientists said that a GRB is the most likely.

“This is exciting, and not just because it probably is the first ‘orphan’ GRB to be discovered. It also is the oldest well-localized GRB, and the long time period during which it has been observed means it can give us valuable new information about GRB afterglows,” Law said.

“Until now, we’ve never seen how the afterglows of GRBs behave at such late times,” noted Brian Metzger of Columbia University, co-author of the study. “If a neutron star is responsible for powering the GRB and is still active, this might give us an unprecedented opportunity to view this activity as the expanding ejecta from the supernova explosion finally becomes transparent.”

“I’m delighted to see this discovery, which I expect will be the first of many to come from the unique investment the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) and the National Science Foundation are making in VLASS,” said NRAO Director Tony Beasley.

VLASS is the largest observing project in the history of the VLA. Begun in 2017, the survey will use 5,500 hours of observing time over seven years. The survey will make three complete scans of the sky visible from the VLA, roughly 80 percent of the sky. Initial images from the first round of observations now are available to astronomers.

VLASS follows two earlier sky surveys done with the VLA. The NRAO VLA Sky Survey (NVSS), like VLASS, was an all-sky survey done from 1993 to 1996, and the FIRST (Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty centimeters) survey studied a smaller portion of the sky in more detail from 1993 to 2002. The astronomers discovered FIRST J1419+3940 by comparing a 1994 image from the FIRST survey to the VLASS 2017 data.

From 2001 to 2012, the VLA underwent a major upgrade, greatly increasing its sensitivity, or ability to image faint objects. The upgrade made possible a new, improved survey offering a rich scientific payoff. The earlier surveys have been cited more than 4,500 times in scientific papers, and scientists expect VLASS to be a valuable resource for research in the coming years.

Law and his colleagues are publishing their findings in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

###

Media Contact:

Dave Finley, Public Information Officer

(575) 835-7302

dfinley@nrao.edu

###