3.10.2018

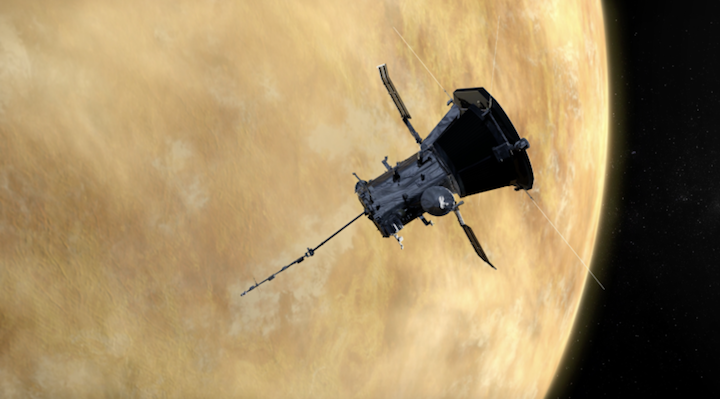

NASA's Parker Solar Probe is swinging by Venus on its unprecedented journey to the sun.

Launched in August, the spacecraft gets a gravity assist Wednesday as it passes within 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) of Venus. The flyby is the first of seven that will draw Parker ever closer to the sun.

By the end of October, Parker will shatter the current record for close solar encounters, set by a NASA spacecraft in 1976 from 27 million miles (43 million kilometers) out. Parker will get within 15 million miles (25 million kilometers) of the sun's surface in November. Twenty-four such orbits — dipping into the sun's upper atmosphere, or corona — are planned over the next seven years. The gap will eventually shrink to 3.8 million miles (6 million kilometers).

Quelle: abcNews

---

Update: 5.10.2018

.

Parker Solar Probe Conducts First Venus Fly-By, On Course For The Sun in Late October

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, launched just under two months ago atop a ULA Delta-IV Heavy rocket from Cape Canaveral, successfully conducted its first gravity-assist around Venus early this morning, October 3, as it makes its way to the sun on a science mission unlike anything we’ve seen before.

Built by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, the car-sized spacecraft will become the fastest human-made object ever when it makes its closest approaches to the sun, traveling at speeds of up to 430,000 miles per hour (700,000 kilometers per hour) as it swoops through the Sun’s atmosphere 24 times over a period of 7 years, or as fast as traveling from New York City to Tokyo in less than one minute.

Using the gravitational tug of Venus to gradually shrink its orbit, the spacecraft will come closer to our star than any spacecraft has before, facing brutal heat and radiation, in order to provide the first ever samplings of a star’s corona, which is visible to the human eye during a total solar eclipse and can reach temperatures upwards of 10 million degrees Fahrenheit.

This morning’s first pass of Venus came within 1,500 miles of the planet’s surface at approximately 4:45am EDT, changing Parker Solar Probe’s trajectory to take it closer to the Sun.

“Detailed data from the flyby will be assessed over the next few days. This data allows the flight operations team to prepare for the remaining six Venus gravity assists which will occur over the course of the seven-year mission”, says NASA.

On Oct 29, it will come within 27 million miles of the Sun, and on October 30 it will surpass a heliocentric speed of 153,454 miles per hour, which is the record for the fastest spacecraft measured relative to the Sun, set by Helios 2 in 1976.

The spacecraft’s first solar encounter will begin on Oct 31, losing contact with Earth as it focuses on collecting valuable science data. Closest approach for this first solar pass will occur on Nov. 5 or 6, followed by re-establishing contact with Earth and downlinking the science data back home throughout last month of the year.

“Parker Solar Probe is going to revolutionize our understanding of the Sun, the only star we can study up close,” said Nicola Fox, project scientist for Parker Solar Probe at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, Maryland. “The mission undertakes one of the most extreme journeys of exploration ever tackled by a human-made object.”

Quelle: AS

----

Update: 14.12.2018

.

Parker Solar Probe: Sun-skimming mission starts calling home

A streamer, a dense part of the corona, moves away from the Sun (out of view to the left)

Just weeks after making the closest ever flyby of the Sun, Nasa's Parker Solar Probe is sending back its data.

Included in the observations is this remarkable image of the energetic gas, or plasma, flowing out from the star.

The bright dot is actually Mercury. The black dots are repeats of the little world that occur simply because of the way the picture is constructed.

Parker's WISPR instrument acquired the vista just 27.2 million km from the surface of the Sun on 8 November.

The imager was looking out sideways from behind the probe's thick heat shield.

The Nasa mission was launched back in August to study the mysteries of the Sun's outer atmosphere, or corona.

This region is strangely hotter than the star's "surface", or photosphere. While this can be 6,000 degrees Celsius, the outer atmosphere may reach temperatures of a few million degrees.

The mechanisms that produce this super-heating are not fully understood.

Parker aims to solve the puzzle by passing through the outer atmosphere and directly sampling its particle, magnetic and electric fields.

"We need to go into this region to be able to sample the new plasma, the newly formed material, to be able to see what processes, what physics, is taking place in there," explained Nicola Fox, director of the Heliophysics Division at Nasa HQ in Washington DC.

"We want to understand why there is this temperature inversion, as in - you walk away from a hot star and the atmosphere gets hotter not colder as you would expect."

Not only is Parker breaking records for proximity to the Sun, it is also setting new speed records for a spacecraft. On the recent flyby, it achieved 375,000km/h. The fastest any previous probe managed was about 250,000km/h.

Parker will go quicker still on future close passes of the Sun..

The latest science from the mission is being featured here at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting - the largest annual gathering of Earth and space scientists.

Quelle: BBC

----

Update: 29.01.2019

.

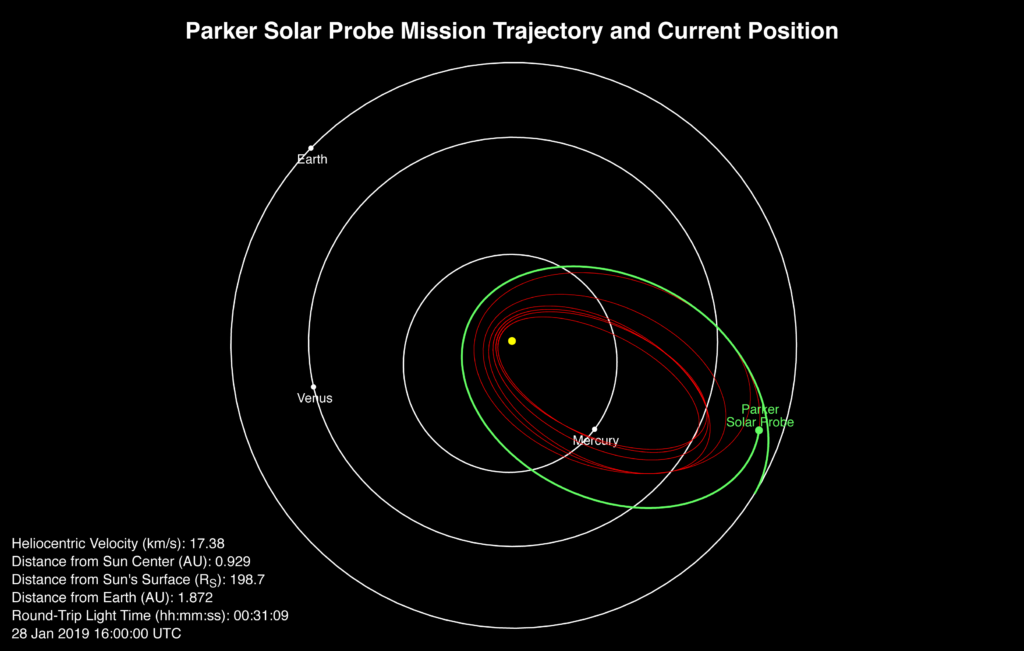

All Systems Go As Parker Solar Probe Begins Second Sun Orbit

On Jan. 19, 2019, just 161 days after its launch from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe completed its first orbit of the Sun, reaching the point in its orbit farthest from our star, called aphelion. The spacecraft has now begun the second of 24 planned orbits, on track for its second perihelion, or closest approach to the Sun, on April 4, 2019.

Parker Solar Probe entered full operational status (known as Phase E) on Jan. 1, with all systems online and operating as designed. The spacecraft has been delivering data from its instruments to Earth via the Deep Space Network, and to date more than 17 gigabits of science data has been downloaded. The full dataset from the first orbit will be downloaded by April.

“It’s been an illuminating and fascinating first orbit,” said Parker Solar Probe Project Manager Andy Driesman, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. “We’ve learned a lot about how the spacecraft operates and reacts to the solar environment, and I’m proud to say the team’s projections have been very accurate.” APL designed, built, and manages the mission for NASA.

“We’ve always said that we don’t know what to expect until we look at the data,” said Project Scientist Nour Raouafi, also of APL. “The data we have received hints at many new things that we’ve not seen before and at potential new discoveries. Parker Solar Probe is delivering on the mission’s promise of revealing the mysteries of our Sun.”

The Parker Solar Probe team is not only focused on analyzing the science data but also preparing for the second solar encounter, which will take place in about two months.

In preparation for that next encounter, the spacecraft’s solid state recorder is being emptied of files that have already been delivered to Earth. In addition, the spacecraft is receiving updated positional and navigation information (called ephemeris) and is being loaded with a new automated command sequence, which contains about one month’s worth of instructions.

Like the mission’s first perihelion in November 2018, Parker Solar Probe’s second perihelion in April will bring the spacecraft to a distance of about 15 million miles from the Sun – just over half the previous close solar approach record of about 27 million miles set by Helios 2 in 1976.

The spacecraft’s four instrument suites will help scientists begin to answer outstanding questions about the Sun’s fundamental physics — including how particles and solar material are accelerated out into space at such high speeds and why the Sun’s atmosphere, the corona, is so much hotter than the surface below.

Quelle: NASA