31.07.2018

Our Sun’s beginnings are a mystery. It burst into being 4.6 billion years ago, about 50 million years before the Earth formed. Since the Sun is older than the Earth, it’s hard to find physical objects that were around in the Sun’s earliest days—materials that bear chemical records of the early Sun. But in a new study in Nature Astronomy, ancient blue crystals trapped in meteorites reveal what the early Sun was like. And apparently, it had a pretty rowdy start.

“The Sun was very active in its early life—it had more eruptions and gave off a more intense stream of charged particles. I think of my son, he’s three, he’s very active too,” says Philipp Heck, a curator at the Field Museum, professor at the University of Chicago, and author of the study. “Almost nothing in the Solar System is old enough to really confirm the early Sun’s activity, but these minerals from meteorites in the Field Museum’s collections are old enough. They’re probably the first minerals that formed in the Solar System.”

The minerals Heck and his colleagues looked at are microscopic ice-blue crystals called hibonite, and their composition bears earmarks of chemical reactions that only would have occurred if the early Sun was spitting lots of energetic particles. “These crystals formed over 4.5 billion years ago and preserve a record of some of the first events that took place in our Solar System. And even though they are so small—many are less than 100 microns across—they were still able to retain these highly volatile nobles gases that were produced through irradiation from the young Sun such a long time ago,” says lead author Levke Kööp, a post-doc from the University of Chicago and an affiliate of the Field Museum.

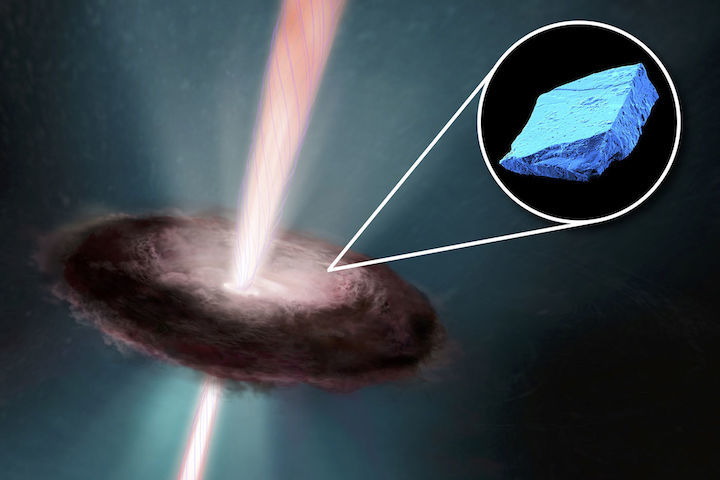

In its early days, before the planets formed, the Solar System was made up of the Sun with a massive disk of gas and dust spiraling around it. The region by the sun was hot. Really hot—more than 1,500 C, or 2,700 F. For comparison, Venus, the hottest planet in the Solar System, with surface temperatures high enough to melt lead, is a measly 872 F. As the disk cooled down, the earliest minerals began to form—blue hibonite crystals.

“The larger mineral grains from ancient meteorites are only a few times the diameter of a human hair. When we look at a pile of these grains under a microscope, the hibonite grains stand out as little light blue crystals—they’re quite beautiful,” says Andy Davis, another co-author also affiliated with the Field Museum and the University of Chicago. These crystals contain elements like calcium and aluminum.

When the crystals were newly formed, the young Sun continued to flare, shooting protons and other subatomic particles out into space. Some of these particles hit the blue hibonite crystals. When the protons struck the calcium and aluminum atoms in the crystals, the atoms split apart into smaller atoms—neon and helium. And the neon and helium remained trapped inside the crystals for billions of years. These crystals got incorporated into space rocks that eventually fell to Earth as meteorites for scientists like Heck, Kööp, and Davis to study.

Researchers have looked at meteorites for evidence of an early active Sun before. They didn’t find anything. But, Kööp notes, “If people in the past didn’t see it, that doesn’t mean it wasn’t there, it might mean they just didn’t have sensitive enough instruments to find it.”

This time, the team examined the crystals with a unique state-of-the-art mass spectrometer in Switzerland—a garage-sized machine that can determine objects’ chemical make-up. Attached to the mass spectrometer, a laser melted a tiny grain of hibonite crystal from a meteorite, releasing the helium and neon trapped inside so they could be detected. “We got a huge signal, clearly showing the presence of helium and neon—it was amazing,” says Kööp.

The bits of helium and neon provide the first concrete evidence of the Sun’s long-suspected early activity. “It’d be like if you only knew someone as a calm adult—you’d have reason to believe they were once an active child, but no proof. But if you could go up into their attic and find their old broken toys and books with the pages torn out, it’d be evidence that the person was once a high-energy toddler,” says Heck.

Quelle: FIELD MUSEUM

---

Update: 1.08.2018

.

Vor gut 4,5 Milliarden Jahren durchlief die Sonne eine aktive Phase, in der sie viel stärker strahlte als heute. Das schliessen Forscher aus neuen Messungen mit einem höchst sensiblen Massenspektrometer der ETH Zürich. Die Wissenschafter der ETH Zürich und der Universität Chicago untersuchten Material des sogenannten Murchison-Meteorits. Dieser wird in der Forschung aufgrund seiner grossen Masse und ursprünglichen Zusammensetzung oft als Standardprobe verwendet, wie aus einer Mitteilung der ETH vom Dienstag hervorgeht. Er enthält unter anderem Einschlüsse, die reich an Kalzium und Aluminium sind und aus der Urzeit des Sonnensystems stammen.

Diese Einschlüsse sind die ersten Minerale, die vor gut 4,5 Milliarden Jahren aus dem solaren Nebel kondensierten. Sie formierten sich nahe der Sonne aus einem 2000 Grad heissen Gasgemisch, das sich abkühlte. Innerhalb weniger Millionen Jahre gelangten sie in äussere Regionen des Sonnensystems, wo sie in Asteroiden eingebaut wurden.

Die Forschenden untersuchten zwei verschiedene Klassen von Einschlüssen und massen deren Gehalt an Helium und Neon. Von diesen Edelgasen gibt es verschiedene Isotope, also Atome mit gleichen chemischen Eigenschaften, aber leicht unterschiedlichen Massen. Da Helium-3 und Neon-21 entstehen, wenn Einschlüsse kosmischer Strahlung ausgesetzt sind, erlaubt deren Analyse Rückschlüsse auf die Bestrahlung, der die Minerale im Weltraum ausgesetzt waren.

Beweis für stärkere Strahlung

«Vom Murchison-Meteorit wissen wir, dass dieser rund 1,5 Millionen Jahre im All unterwegs war, bevor er 1969 in Australien auf die Erde stürzte», erklärt Henner Busemann, wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Departement Erdwissenschaften der ETH, laut Mitteilung. Auch eine der beiden untersuchten Klassen von Einschlüssen wies das gleiche Bestrahlungsalter auf.

Die andere zeigte allerdings deutlich höhere Werte von Helium-3 und Neon-21. Diese Klasse habe also nach ihrer Bildung und vor dem Einbau in den Mutterasteroiden von Murchison eine zusätzliche Bestrahlung bekommen, so der ETH-Forscher.

Dafür gibt es nur eine Erklärung: Die Sonnenstrahlung, die auch aus Teilchen besteht, muss bei der Entstehung dieser Minerale mindestens 50 mal stärker gewesen sein als später, als die andere Klasse der Einschlüsse und das restliche Material des Murchison-Mutterkörpers kondensierten.

Dass die junge Sonne eine solch aktive Phase durchlaufen habe, sei zwar schon aufgrund früherer Messungen von Meteoritenmaterial vermutet worden, doch erst jetzt habe man einen stichhaltigen Beweis dafür, so Busemann. Ähnlich aktive Phasen kann man heute bei jungen, sonnenähnlichen Sternen beobachten, die verstärkt Röntgen- und Teilchenstrahlung in Form von Jets aussenden. Über ihre Befunde berichteten die Forschenden im Fachjournal «Nature Astronomy».

Alt aber empfindlich

Möglich machte die genaue Messung ein am Institut für Geochemie und Petrologie der ETH Zürich vor 20 Jahren gebautes Instrument. Die Geophysikerin und Erstautorin der Studie, Levke Kööp von der Universität Chicago, reiste deswegen extra nach Zürich. Denn die Proben, die aus der frühesten Geschichte des Sonnensystems stammen, sind sehr klein. Deswegen waren kleine Edelgasmengen zu erwarten.

Das Zürcher Massenspektrometer ist weltweit nach wie vor das einzige Instrument, das solch geringe Konzentrationen bestimmter Edelgase nachweisen kann. Bei Helium- und Neonmessungen ist es um einen Faktor 100 empfindlicher als kommerzielle Geräte.