30.05.2018

Drew Feustel will be the 22nd U.S. citizen to command the International Space Station (ISS). After the completion of his tenure, no U.S. astronaut is slated to command the station throughout 2019. Photo Credit: NASA

-

When Expedition 56 astronaut Drew Feustel relinquishes the helm of the International Space Station (ISS) to Germany’s Alexander Gerst, early in October, more than a year will elapse with no U.S. citizen in command of the multi-national orbiting outpost. From that date, and throughout the entirety of 2019—for the first time in the station’s two-decade history—we will see a 12-month calendar year without a U.S. ISS Commander. NASA has revealed that no fewer than two European Space Agency (ESA) astronauts will command the ISS during this period, together with three Russian cosmonauts.

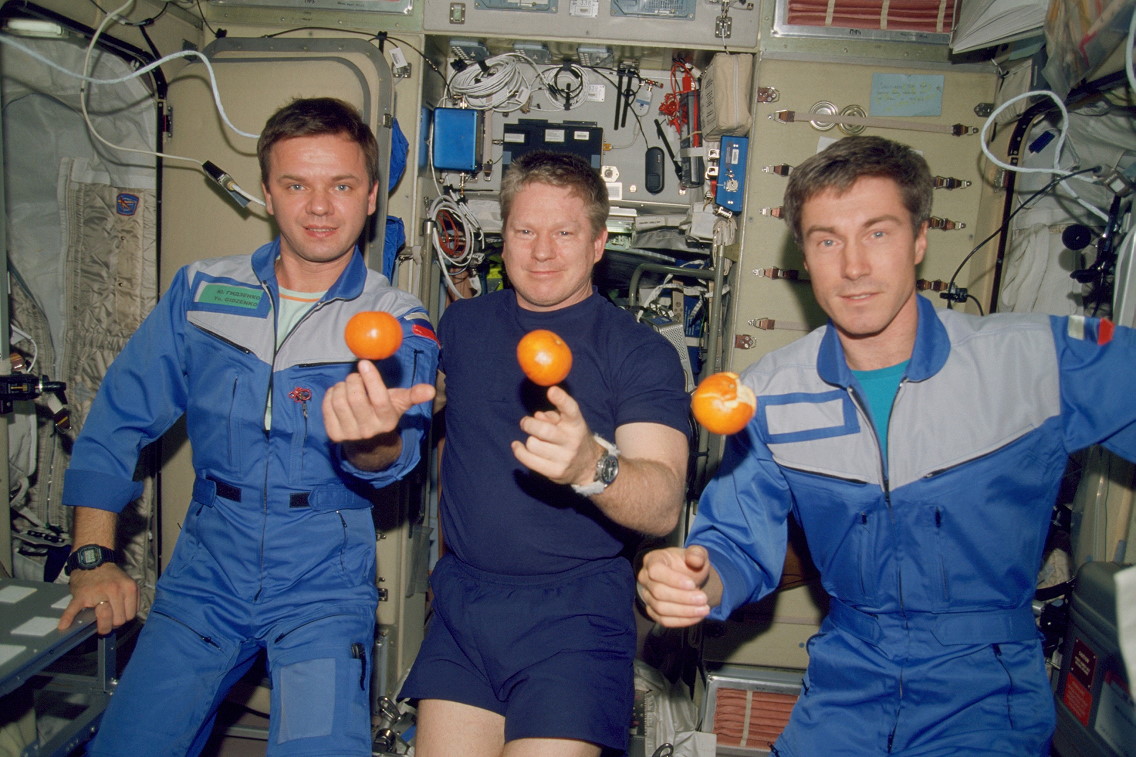

Expedition 1 Commander Bill Shepherd (center) was the first skipper of the International Space Station (ISS), during the fall of 2000 and spring of 2001. Photo Credit: NASA

From the very start, the United States’ contribution to the ISS Program was recognized when a NASA astronaut—veteran shuttle flyer Bill Shepherd—was named in early 1996 to command the station’s first long-duration increment. He launched in October 2000, shoulder-to-shoulder with a pair of Russian cosmonauts, and led Expedition 1 until March of the following year. Since then, every calendar year has seen at least one U.S. astronaut at the helm of the station. All told, and including Feustel, who will take command of Expedition 56 next week, 21 U.S. astronauts have led the ISS, three of whom—Jeff Williams, Scott Kelly and former Chief Astronaut Peggy Whitson—have done so on more than one occasion. Key years included 2001, when Frank Culbertson was the only U.S. citizen off the planet during the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and 2007-2008, when Whitson became the first woman in history to command a space station.

With Feustel’s return home on 4 October, German astronaut Alexander Gerst of ESA will take command of Expedition 57, leading the ISS through his own landing on 13 December. His crew will initially comprise three members—Russian cosmonaut Sergei Prokopiev and NASA’s Serena Auñón-Chancellor—before Soyuz MS-10 launches on 11 October, carrying Russia’s Alexei Ovchinin and U.S. astronaut Nick Hague. Originally, a second cosmonaut was also assigned to MS-10, but for the second time in under two years, the unfortunate Nikolai Tikhonov has been removed from a prime crew, due to delays with Russia’s long-awaited Nauka (“Science”) Multipurpose Laboratory Module (MLM). A similar situation occurred in 2017, where vacant seats on Soyuz MS-06 and MS-08 were filled by additional U.S. astronauts. However, according to NASA’s Rob Navias, there are no plans for the vacant third seat on MS-10 to be occupied by an extra U.S. crew member.

The Expedition 57 crew will be led by Germany’s Alexander Gerst (seated, center). He will become only the second European to lead the station. His crewmates include (from left) Serena Auñón-Chancellor, Alexei Ovchinin, Nick Hague and Sergei Prokopiev. Photo Credit: NASA, via Joachim Becker/SpaceFacts.de

When Gerst, Prokopiev and Auñón-Chancellor return to Earth in December, command of the ISS will pass to Ovchinin, who will lead Expedition 58 as a two-man crew for about a week—marking the first time since the beginning of Expedition 22 in December 2009 that the station’s crew has been temporarily reduced to such a low number—ahead of the arrival of Soyuz MS-11 and Russian cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko, Canada’s David Saint-Jacques and U.S. astronaut Anne McClain on the 20th. Soyuz MS-12 is slated to launch on 5 April 2019, carrying two new crew members uphill in a relatively rare “direct handover” operation and temporarily boosting Expedition 58 to seven-strong. Ten days later, MS-10 will return Ovchinin and Hague back to Earth, after 186 days in space. Kononenko will then take command of Expedition 59, through his own crew’s return home on 8 July, wrapping up 200 days in orbit.

Until recently, it was expected—though formally unannounced—that ISS veteran Shannon Walker would fly aboard MS-12, alongside Russian cosmonauts Oleg Skripochka and Andrei Babkin. Walker had initially been assigned in March 2017 as dedicated backup to Joe Acaba, when he was inserted onto the MS-06 crew at short notice. Last October, the Multilateral Crew Operations Panel (MCOP) approved Walker’s assignment to MS-12. However, earlier in 2018, it became clear that both Babkin and Walker had been removed from MS-12 and, last week, NASA announced that “rookie” astronaut Christina Hammock-Koch would join Skripochka on this crew. According to NASA, Walker’s current role is Chief of the Assigned Crew Branch within the Astronaut Office.

“Humbled, awed and excited to be back training again with our partners in Russia,” Hammock-Koch tweeted last week. “Reminders of their incredible achievements in space keep the motivation and perspective real!” With a third seat now vacant on MS-12, Mr. Navias told AmericaSpace that there are “no plans” for an additional U.S. crew member to fly aboard the mission.

Due to launch in December 2018, the Soyuz MS-11 crew comprises (from left) Anne McClain, Oleg Kononenko and David Saint-Jacques. Photo Credit: NASA

When Kononenko, Saint-Jacques and McClain land in early July, Skripochka will take command of Expedition 60 and lead ISS operations until he and Hammock-Koch return to Earth on 22 October, concluding a 200-day increment. After a few days as a two-member crew, Soyuz MS-13 will launch on 15 July, carrying Russian cosmonaut Aleksandr Skvortsov, Italian ESA astronaut Luca Parmitano and NASA’s Drew Morgan. When Skripochka and Hammock-Koch depart on 22 October, Parmitano will command Expedition 61 until his own crew returns to Earth in late January 2020. Shorly thereafter, Soyuz MS-13 will launch with two Russians and an as-yet-unnamed U.S. astronaut. In doing so, Parmitano will be the third European—after Belgium’s Frank de Winne and Germany’s Alexander Gerst—to command the station and the first Italian to do so. Parmitano also became Italy’s first spacewalker, during his first flight in 2013.

With this line-up of commanders—Gerst from October to December 2018, Ovchinin from December 2018 until April 2019, Kononenko from April to July 2019, Skripochka from July to October 2019 and Parmitano from October 2019 to January 2020—the ISS will thus see no U.S. astronaut in command throughout 2019.

Luca Parmitano, seen here during Italy’s first spacewalk in July 2013, will become the first Italian citizen to command the International Space Station (ISS) in 2019-2020. Photo Credit: NASA

It is not unusual to see long “runs” of U.S. Orbital Segment (USOS) or Russian Orbital Segment (ROS) commanders, usually agreed for operational reasons between the International Partners (IPs) at MCOP level, and, indeed, a 14-month period elapsed without an American commander between the landing of Expedition 34’s Kevin Ford in March 2013 and the start of Steve Swanson’s tenure at the helm of Expedition 40 in May 2014. However, it is notable that 2019 looks set to be the first full calendar year since 2000 that no U.S. astronaut will command the station. “Although they are with ESA, Gerst and Parmitano are considered “USOS” crew members, as all IPs other than Russia are,” NASA’s Brandi Dean noted. “The commander duties generally alternate between Russian commanders and USOS commanders, not specifically NASA commanders.”

Moving forward, it is expected that ISS expeditions will run for 180-200 days apiece—about a month longer than standard—as NASA and the IPs ready themselves for the test-flights and Post-Certification Missions (PCMs) of the Commercial Crew Program (CCP). “We and Roscosmos agreed to extend the increments to about 180 days or so,” Mr. Navias told AmericaSpace, “to ensure that we will be making a seamless inclusion of CCP flights to blend in with Soyuz operations.”

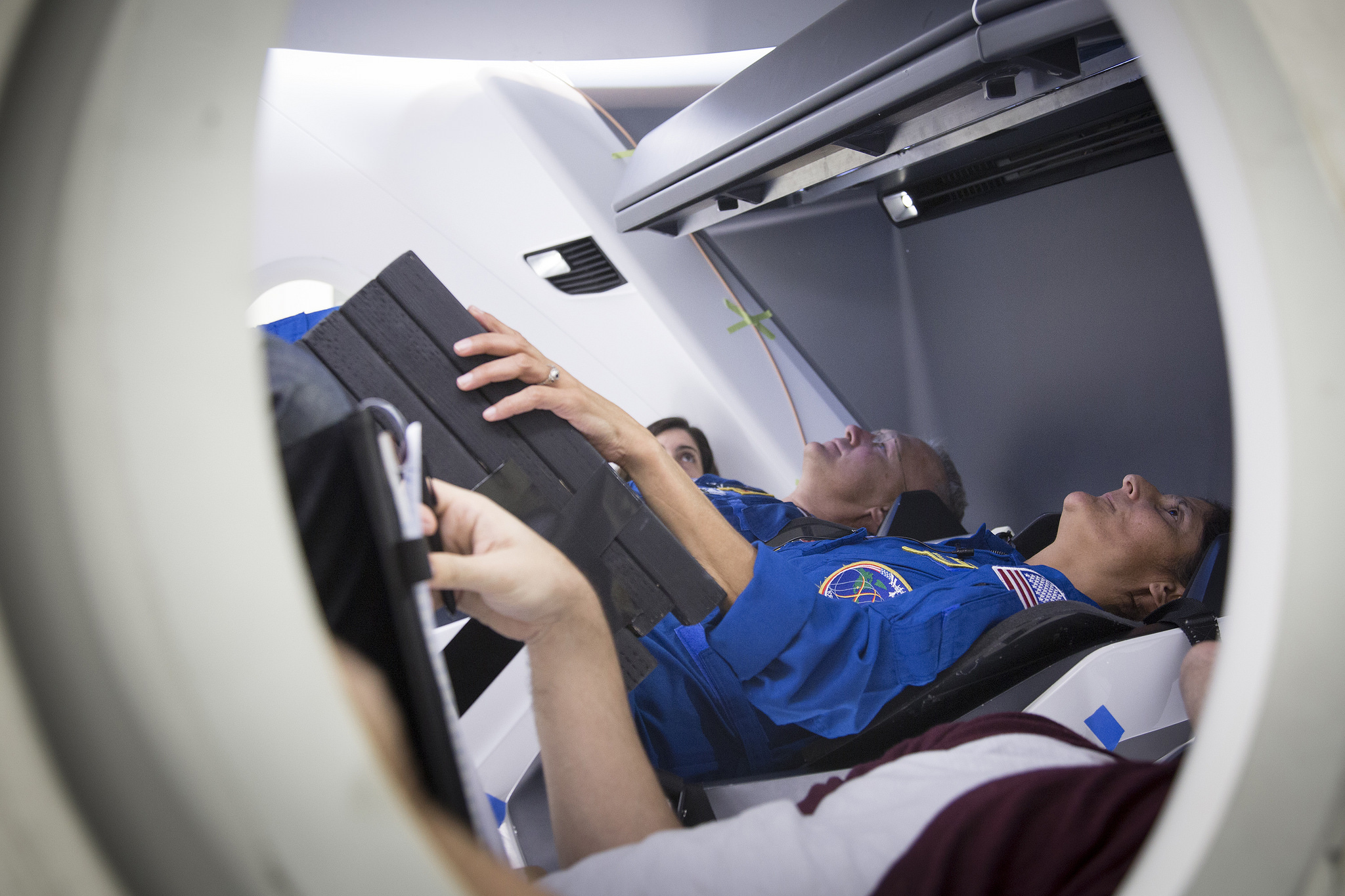

NASA astronauts Doug Hurley, center, and Sunita “Suni” Williams sit inside a Crew Dragon mockup during an evaluation visit for the Crew Dragon spacecraft at SpaceX’s Hawthorne, Calif., headquarters. Photo Credit: SpaceX

Those Commercial Crew missions presently remain in flux, with the unpiloted test-flights of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon and Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner targeted for launch in August 2018, followed by piloted test-flights at year’s end or, more likely, in the first quarter of 2019. Although veteran NASA shuttle and ISS flyers Eric Boe, Doug Hurley, Sunita Williams and former Chief Astronaut Bob Behnken were assigned to the test-flight program in July 2015, it remains to be seen which missions they will actually fly.

“The specific flight assignments for the first Commercial Crew flights haven’t been made yet,” Ms. Dean told AmericaSpace, “but it is not a given that the four “commercial crew cadre” members will be on the first two flights—they may be spread among the first several flights. At this point, everyone has been participating in work on both vehicles and they’ll start focusing on one or the other once they’ve been assigned to a specific flight. And there is a certain amount of space station training that everyone will need, as well.”

Originally, both piloted test-flights were baselined at a duration of about 14 days, but earlier this year Boeing’s contract was modified to permit a longer mission of up to six months. “NASA updated its Commercial Crew transportation Capability (CCtCap) contract with Boeing [on] 30 March,” NASA’s Stephanie Martin told AmericaSpace. “The update includes the ability to extend Boeing’s Crew Flight Test from roughly two weeks to up to six months, as well as the training and mission support for a third crew member. Expanding the original scope of the test-flight needs additional careful technical review by NASA and Boeing. The new capability can allow the docked duration of the spacecraft and, more importantly, the critical additional crew, to remain on-orbit for a longer period of time to enable additional microgravity research, maintenance and other activities.”

An artist’s illustration depicting the approach of a SpaceX Crew Dragon to the International Space Station (ISS). Image Credit: SpaceX

Current plans are for the Crew Dragon test-flight to remain at two weeks in length. “If SpaceX also submits a proposal to extend their stay on station during their flight-test with crew, the agency will review it through the normal procurement process, as NASA did for Boeing,” added Ms. Martin.

Primary objectives of both test-flights are to validate spacecraft systems. “During the demos, crew members will have the ability to interface with spacecraft displays and controls, communicate with mission control and the space station, monitor the spacecraft’s largely autonomous rendezvous, docking, and re-entry capabilities and assess on-orbit functions for crew health and hygiene,” Ms. Martin told AmericaSpace. “After successful completion of the flight tests with crew, NASA will review flight data to verify the systems meet certification requirements and are ready to begin regular servicing missions to the space station.”

After the piloted test-flights, the plan for Post-Certification Missions (PCMs)—which will operationally rotate ISS astronauts and cosmonauts and create the capability to increase the ISS long-duration crew from six to seven permanent members—also remains in flux, although it is expected that the first U.S. Crew Vehicle (USCV-1) will fly as a SpaceX Crew Dragon as early as April 2019. This spacecraft, the contract for which was awarded by NASA back in November 2015, is expected to include two crew members and remain docked at the station for about a month, with USCV-2, utilizing Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner, slated to launch in May 2019 for a full six-month docked period. This will be Boeing’s first PCM and its contract was awarded back in May 2015. Another mission, USCV-3, featuring the second PCM of a Crew Dragon, is targeted to loft four crew members as early as November 2019. Upon arrival at the space station, these additional astronauts and cosmonauts will fold into the incumbent ISS crews.

Quelle: AS